The Undercount of Young Black Children in the U.S. Census

By

Dr. William P. O’Hare

President of O’Hare Data and Demographic Services LLC

And Consultant to the Count All Kids Complete Count Committee

Executive Summary

For many decades the Black population has been missed in the U.S. Census at a high level. While there has been considerable focus on the high net undercount of the Black adults, relatively little attention has been focused on young Black children

A quick examination of the Census counts for the total Black population, shows that despite improvements in the past 70 years, the net undercount for the Black population (2.5 percent) was higher than any other race group in the 2010 Census.

The net undercount rate for young Black (Alone or in Combination) children was 6.3 percent which is about 50 percent higher than the net undercount rate for all young children. A very large segment (48 percent) of young Black children are living in Census tracts where there is a very high risk of a young child net undercount in the 2020 Census. The percent of young Black children in very high risk of undercount Census tracts is higher than any other race/Hispanic group. The percent of young Black children living in very high risk of undercount Census tracts is more than five times that of young Non-Hispanic White young children. Young Black children living in very high risk of undercount Census tracts are very concentrated geographically. Half of all such young Black children are located in just 25 counties and one-quarter are located in just nine counties. Doing a good job of counting young Black children in these places would go a long way toward reducing the overall net undercount of young Black children.

There is no single reason why young Black children are missed at such a high rate. However, one reason young Black children are missed at a high rate is related to the fact that about one-quarter of low-income Black parents are not certain young children are supposed to be included in the Census. Also, young Black children are more concentrated in living arrangements and family structure situations that are linked to be missed in the Census. The high net undercount of young Black children in the Census means the communities where they live will not get their fair share of the $1.5 trillion the U.S. government distribute to states and localities every year based on the Census.

In addition to being missed at a high rate in the Census, young Black children are also missed in Census Bureau surveys at a higher rate than others.

The Undercount of Young Black Children in the U.S. Census

1.Introduction

For many decades the Black population has been missed in the U.S. Census at a very high rate. The high net undercount of Blacks has been among the most contentious issues faced by the Census Bureau over the past half century. However, within these discussions and debates relatively little attention has been paid to vulnerable position young Black children. This paper focuses on the count of young Black children in the Census including the high net undercount in the 2010 Census, trends over time, geographic distribution of vulnerable young Black children, and a discussion of some of the reasons for the high net undercount of this population.

The main intent of this paper is to make critical data easily available to readers. There is not a lot of information on this issue to begin with, but equally important, a lot of the statistics and studies on this issue are not easy to find. My goal here is to make key information on this topic more readily available to people who are interested in the high net undercount of young Black children.

Although all the direct measures of Census accuracy presented in this paper reflect net undercounts, it is important to recognize that net undercounts are not the same as omissions or people being missed (O’Hare 2019b). In short, the net undercount rate is a balance of people missed and people double counted. The number of people missed is almost always higher than the net undercount. See Appendix A for more information on this issue.

2.2010 Census Counts for the Black Population

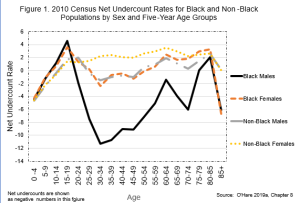

Historically, the Census Bureau has struggled to accurately count both Black adults and Black children. Before looking more specifically at the Census count of young Black children, it is worth taking a closer look at the accuracy of Census counts for the total Black population. Figure 1 shows the net undercount rates in the 2010 Census for Blacks and non-Blacks by age and sex.

Early in life and late in life there are not big differences in the coverage rates of Black males and the other three race/sex groups shown in Figure 1. However, starting in their early 20s into their 70s, the undercount differentials between Black Alone males and the other three groups are substantial. For example, at age 30 the difference in Census coverage rates between Black Alone males and Black Alone females is about 8 percentage points (net undercount rate of 8.3 percent for 30-year-old Black Alone males and 0 percent for 30-year-old Black Alone females.)

This pattern is not new. High net undercount rates for Black men have been a persistent problem in the U.S. Census (Runes, 2019; Fein 1989; Hill 1975; Passel 1991; Robinson et al. 1990; Robinson 1997; U.S. Census Bureau 1988; and West et al. 2014). A report following the 1990 Census (U.S. Census Bureau 1991, page 1) states,

“To summarize, two groups stand out as having relatively high levels of net undercount nationally after considering the possible range of uncertainty in the estimates: 1) Black children aged 0-9 and 2) Black men aged 20-64.”

This problem identified in the 1990 Census is still very much with us.

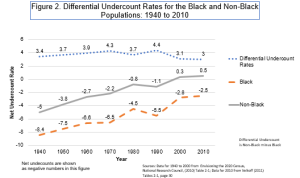

Figure 2 shows trends from 1940 to 2010 in Census coverage of the Black population relative to the non-Black population. There are no consistent data for the White population over this time period so comparing the data for the Black population to that of the non-Black population is the best comparison available.

In some ways the changes in the Census coverage rates for the Black population over the past 70 years is a “good news/bad news” story. The good news is that the net undercount rate for the Black population has decreased dramatically since 1940. The bad news is that the difference between Census coverage rates for the Black population and non-Black population has changed very little over that time period.

Figure 2 shows the net undercount rate for the Black population has gone from 8.4 percent in 1940 to 2.5 percent in 2010. While this is a substantial improvement in Census coverage since 1940, the Black net undercount rate in 2010 is still the highest of any major racial/ethnic group (O’Hare 2019a, Chapter 4). Moreover, despite this substantial improvement in the Census coverage of the Black population since 1940, the differential undercount between Blacks and non-Blacks has not changed much. Figure 2 shows the differential undercount (Non-Black undercount rate minus the Black undercount rate) was 3.4 percentage points in 1940 and 3.0 percentage points in 2010.

However, the short-term story (1990 to 2010) is somewhat different than the long -term story (1940 to 2010). The net undercount rate of 5.5 percent for Blacks in the 1990 Census fell to 2.5 percent in the 2010 Census. This is a dramatic decrease over a relatively short period in Census-taking terms. I am not aware of any report or study focused on the dramatic improvement in the Census coverage of the Black population between 1990 and 2010.

It is possible the Census coverage improvement is related to expanded outreach activities such as the Census Partnership Program and paid advertising which started in the 2000 Census. If the increased funding of the Census after 1990, which resulted in expansion of outreach programs, is responsible for the progress seen in a more accurate count of the Black population, the fact the 2020 Census has been underfunded may have a negative impact on the accuracy of the 2020 count for the Black population.

It is also possible the large-scale incarceration of Black men resulted in a lower net undercounts. People in prisons are typically counted very accurately. If the incarceration of Black men is an important reason for the improvement the Census coverage of the Black population since 1990, it could mean the population outside of jails and prisons may be missed a higher rate than reflected in the overall data for all Black men.

Finally, changes between 1990 and 2010 in the way data on race has been collected may be related to the changes in net undercount of the Black population since 1990.

3. The Count of Young Black Children in the Census

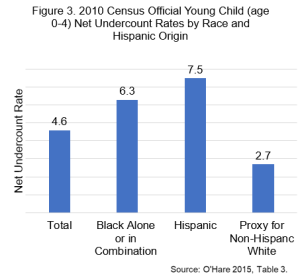

Figure 3 below shows the net undercount rate for young (age 0-4) Blacks in the 2010 Census along with net undercount rates for the total population and Hispanics. Since there are no direct calculations of net undercounts for Whites or non-Hispanic Whites, I calculated number for a proxy population of non-Hispanic White children in this age range. The proxy population includes everyone who is not Black or Hispanic.

The net undercount for young Blacks (Alone or in combination) was 6.3 percent which is about 50 percent higher than that for all children age 0 to 4. Note this figure reflects an inclusive conceptualization of Black children in that it includes those who were identified as Black Alone or any child that was identified as Black as well as some other race. (For a more detailed undercount data for different conceptualizations of the Black population see O’Hare 2015, Table 3.2).

Analysis by the Census Bureau shows that there was a net undercount of about 247,000 young Blacks (Alone or in combination) children in the 2010 Census. This amounts to about a quarter of the net undercount of all young children in the 2010 Census. Unlike adults, there is no difference among young children in terms of gender.

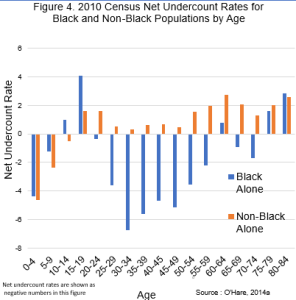

Figure 4 provides 2010 Census data for Blacks compared to non-Blacks by five-year age groups. There are a couple of similarities between Blacks and others and some areas where they differ. The net undercount rate of young Black children is high like that for other groups and young Black children are missed at a higher rate than older Black children, similar to the non-Black population. These data underscore why it is important to focus on young children rather than all children.

However, non-Black young children had a higher net undercount rate than any other age group, but this is not true for the Black population. Blacks in their 30s and 40s had net undercount rates comparable or higher than those of young Black children. As shown in Figure 1, the high net undercount for Blacks from age 20 to 70 is largely driven by the high net undercount of Black men. While the high net undercount of Black men has received a lot of attention, the high net undercount of young Black children has received much less attention even thought their net undercount rates are similar.

The data just presented reflects experiences in past Censuses, but what is more important is what is likely to happen in the 2020 Census. What is the risk of young Black children being missed in the 2020 Census?

One recent study based on demographic changes since 2010, forecasts higher net undercount rates in the 2020 Census compared to the 2010 Census (Elliott et al. 2019). There are no data for young Black children in the study referenced above, but the study predicts the net undercount rates for young children will increase by as much as 50 percent and the net undercount rates for the total Black population will increase by as much as 50 percent.

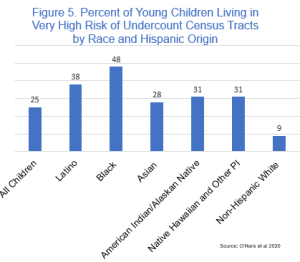

As we approach the 2020 Census, research indicates that almost 1.2 million young Black children live in very high risk of undercount Census tracts (Population Reference Bureau 2020). Very high risk of undercount Census tracts are those where the predicted net undercount rate for young children will be 8.3 percent or higher. This is about twice the overall net undercount rate for all young children in the 2010 Census.

Figure 5 shows nearly half (48 percent) of all young Black children live in Census tracts where they have a very high risk of being undercounted in the 2020 Census and that is a much higher percentage than any other race or ethnic group. The percent of young Black children living in very high risk of undercount Census tracts, is more than five times higher than that for young Non-Hispanic White Alone children. (The Population Reference Bureau tract-level database is available here https://www.prb.org/new-strategies-to-reduce-undercount-of-young-children-in-2020-Census/)

In addition to the 1.2 million young Black children in very high risk of undercount tracts, there are another 1.1 million young Black children are living in Census tracts where they have a high risk of being undercounted in the Census (data not shown here). These are Census tracts where a net undercount is predicted, but not as high as the 8.3 percent for the very high risk of undercount Census tracts.

3. Trends Over Time in the Count of Young Black Children

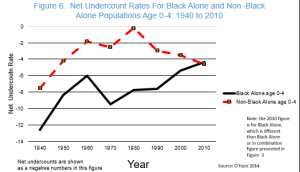

Figure 6 shows the net undercount rate for young children by race from 1940 to 2010. Note the data shown here reflects “Black Alone” rather than the “Black Alone or in Combination” as shown in Figure 3. Black Alone is used here because Black Alone or in Combination data were not available prior to the 2000 Census. Using data for the Black Alone population in this figure allows us to assemble a consistent data set over time.

The net undercount rate for young Black children has improved dramatically since the 13 percent net undercount rate seen in the 1940 Census but is still unacceptably high. In assessing the comparison shown in Figure 6, it is also important to keep in mind that the “Not Black Alone “population has changed over time. In the most recent Census, the not Black Alone population include a growing number of Hispanics which is a group that also experienced high net undercounts in the Census (O’Hare et al. 2016). There is no data for the White or non-Hispanic White population.

4)Where are young Black children most at risk of being undercounted?

The 1.2 million young Black children most at risk of being missed in the 2020 Census are clustered in a relatively small number of counties. Table 1 shows that half of all young Black children living in Census tracts with a very high risk of being undercounted are located in just 25 counties and one-quarter of all young Black children in very high risk of undercount Census tracts are in just nine counties. These locations deserve special attention in terms of reducing the high net undercount of young children in the 2020 Census.

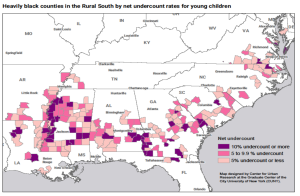

While the biggest concentration of young Black children at risk of being missed in the Census is in large urban areas, there are also several “hot spots” in the rural South where young Black children are vulnerable (O’Hare 2019c and 2019d). The map below shows counties in the rural South where young Black children are most vulnerable of being missed in the Census. Theses counties are concentrated in the Black Belt from South Carolina to Louisiana with a particularly heavy concentration of the hardest to count counties in the Mississippi Delta and another one in southeast Alabama.

View Map Here

Map 1 Rural Counties in the South where young Black children are most at risk of being undercounted

5)Why Are Young Black Children Missed in the Census?

There is no consensus on why young children are missed in the Census at such a high rate and the same can be said for young Black children. Most experts think there are probably many reasons. A few of the more prominent ideas are explored below.

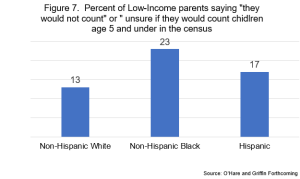

Evidence about one key reason young children are missed in the Census has only recently become available through a survey of low-income (less than $50,000 a year) parents of young children (O’Hare and Griffin, forthcoming). Figure 7 shows that a high percentage of parents of young children are not sure they are supposed to include a young child in the Census. The problem is larger among Black parents. While 13 percent of low-income Non-Hispanic White parents say they would not or might not include their young children in the Census, the figure is 23 percent for Black parents. With such a high rate of parents saying they are not sure they would include their young children in the Census questionnaire, it is not too surprising that so many young children are missed in the Census. The higher rate for the Black population may reflect a lower level of trust in government.

Respondents in this survey were also asked why they thought young children might be left out of a Census questionnaire and the two most common responses were confusion on the part of the respondent about whether the Census Bureau wants young children included and respondents believing there is no reason the government needs to know about a young child in the household. In this context, it is important to remind respondents that Census data are used to distribute more than $1.5 trillion dollars to states and localities each year and many of the programs supported with those funds are focused on children.

In another part of the survey mentioned above, half of the sample were given instructions about how the Census Bureau wants people to think about who to include in their Census questionnaire, and the other half of the sample were not give these instructions. When data were compared, the half of the survey that received the instructions were not any more likely to include young children than those who did not receive the instructions. This suggests that many respondents have an idea in their head about who they think should be included in the Census, and it will take something more than simple written instructions to change that perception. A robust outreach and educational campaign focused on young children might be helpful.

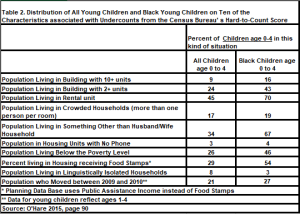

Another reason young Black children are undercounted at a higher rate than others, is linked to their living arrangements and household characteristics. The Hard-to-Count (HTC) score developed by the Census Bureau in the 1990s to identify areas where it would be more difficult to get an accurate enumeration was based on six population characteristics and six housing characteristics thought to be associated with being missed in the Census (Bruce and Robinson 2003). It was not possible to calculate two of these twelve measures for individuals, but Table 2 provides data for ten of those characteristic, for all young children and young Black children. Young Black children are more highly concentrated in hard-to-count situations than young children generally. Of the ten characteristics, young Black children are more concentrated than all children on all of the measures except living in a linguistically isolated household.

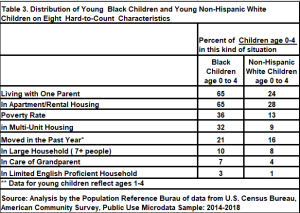

Similar updated information was recently provided by the Population Reference Bureau. Table 3, which is based on the most recent data available, shows data for Black (Alone) compared to Non-Hispanic White Alone young children for eight characteristics thought to be associated with being missed in the Census. For each of the eight hard-to-count situations the percentage of young Black children is higher than that of Non-Hispanic White children: sometimes the differences are small and sometimes they are large, but they are all consistently in one direction.

6)Census Bureau Surveys

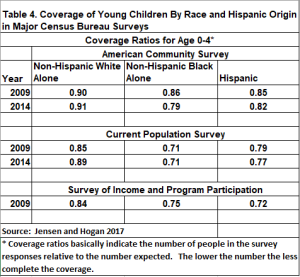

Although the Decennial Census is our focus right now, it is important to note that young children are also missed at a high rate in major Census Bureau surveys and young Black children are missed at a higher rate than others (Jensen and Hogan 2017). Table 4 shows coverage ratios by race and Hispanic Origin for three major Census Bureau surveys. The lower the coverage ratio, the more young children are under-reported.

The figures in Table 4 show that the under-coverage of young Black children is pervasive. Data shown in Table 4 indicate young Black children have lower coverage ratios than the Non-Hispanic White Alone population across the board.

In analyzing coverage ratios for major Census Bureau surveys, the Census Bureau (2019, page 5 ) concludes,

“In three Census Bureau surveys, the estimated coverage rates were lower (indicating greater coverage error) for Hispanic young children and non-Hispanic Black young children compared with non-Hispanic White children.”

I highlight this finding here, because it underscores the need to focus on the undercounting and under-reporting of young Black children in government surveys as well as the Census. The Census only happens once every ten years, but the Census Bureau surveys are done every year. Moreover, these survey provide data on key characteristics like poverty, education, and family structure.

7)Conclusions

Data presented here highlight the high net undercount of young (age 0 to 4) Black children in the U.S. Census. The net undercount rate for Black (Alone or in combination) children under age 5 in the 2010 Census was 6.3 percent which is about 50 percent higher than the rate for all young children.

Some of the reasons for the high net undercount of young Black children are also explored in this paper. Since the data indicate nearly one-quarter of low-income parents of young Black children are not sure young children are supposed to be included in the Census, a strong education and outreach campaign aimed directly at correcting this mis-perception could help get a better count of young Black children in the 2020 Census. Outlining the money brought back to the community for children’s programs with a complete Census count could also be useful.

The chronic high net undercount of young children and the very high net undercount of young Black children indicate these populations should be a high priority in the 2020 Census.

Appendix A – Net Undercounts Do Not Reflect People Missed

It is important to recognize that net undercounts do not represent the number of people missed in the Census. Even though “net undercounts” and “omissions” sound like the same thing, they are not the same in demographic terms.

In the simplest terms, omissions reflect the number of people missed in the Census. Omissions are defined by the U.S. Census Bureau (2012. page 12) as, “people who should have been enumerated in the United States Census but were not.”

Net undercounts (and overcounts) reflect a balance between two groups of people. The first group is those who are omitted from the enumeration as defined above. The second group includes erroneous enumerations and whole-person imputations. Erroneous enumerations are mostly people who have been double counted, but also include people who were counted in error, such as foreign tourists or people included in the count even though they died before April 1 of the Census year.

Whole-person imputations are people who are not directly enumerated but added to the Census count based on some evidence they exist. For example, if a housing unit looks occupied but does not return its Census questionnaire or respond to repeated visits from a Census Bureau enumerator, the Census Bureau may impute people from that housing unit into the Census count.

If the number of omissions is larger than the number of erroneous enumerations and whole-person imputations, there is a net undercount. If the number of erroneous enumerations and whole-person imputations is larger than the number of omissions, there is a net overcount.

There are no data for young child omissions by race but for all young children the number of omissions is about twice as high as the net undercount (U.S. Census Bureau 2016). Data from the Census Bureau indicate the net undercount of young children was about 970,000 compared to one estimate of 2.2. million omissions for this age group. That ratio should be kept in mind as readers see net undercount numbers in this paper.

References

Elliott, D., Santos, R., Martin, S. and Runes, C. (2019) “Assessing Miscounts in the 2020 Census, The Urban Institute, Washington, .DC., https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/100324/assessing_miscounts_in_the_2020_Census.pdf

Bruce, A., and Robinson, J.G., (2003). “The Planning Database: Its Development and use as an Effective tool in Census 2000,” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Southern Demographic Association, Arlington, VA.

Fein, D.J. (1989). The social sources of Census omission: Racial and ethnic differences in omission rates in recent U.S. Censuses” Dissertation in Department of Sociology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ.

Hill, R.B., (1975). Estimating the 1970 Census Undercount for State and Local Areas, National Urban League, Washington, DC.

Jensen, E. and Hogan, H. (2017). “The coverage of young children in demographic surveys,” Statistical Journal of the International Association of Official Statistics (IAOS), Vol 33. pp 321-333. https://content.iospress.com/articles/statistical-journal-of-the-iaos/sji170376?resultNumber=2&totalResults=217&start=0&q=Jensen&resultsPageSize=10&rows=10

O’Hare, W .P. and Griffin, D. (forthcoming). “Are Census Omissions of Young Children Due to Respondent Misconceptions about the Census?”, Poster at the 2020 Population Association of American Conference, Washington DC.

O’Hare W. P. (2019a). Differential Undercounts in the U.S. Census: Who is Missing? Springer publishers, available open access at https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-10973-8

O’Hare, W.P. (2019b). “Understanding Who Was Missed in the 2010 Census” Population Reference Bureau Washington DC. https://theCensusproject.org/2019/08/19/understanding-omissions-in-the-decennial-Census/

O’Hare W.P. (2019c) Counting Young kids in the South in the 2020 Census , The Census Project, https://theCensusproject.org/2019/11/08/counting-young-kids-in-the-south-for-the-2020-Census/

O’Hare W. P. (2019d). “The Census Undercount of Young Children in the South,” Presentation at the Southern Demographic Association Conference,

O’Hare, W.P., Mayol-Garcia, Y., Wildsmith, E., and Torres, A., (2016) The Invisible Ones: How Latino Children Are Left Out of Our Nation’s Census Count, Child Trends Hispanic Institute & National Association of Latino Elected Officials, Child Trends, Washington DC.

O’Hare, W.P. (2015). The Undercount of Young Children in the U.S. Decennial Census. Springer Publishers

O’Hare, W.P. (2014). “Assessing Net Coverage Error for Young Children in the 2010 U.S. Decennial Census.” Center for Survey Measurement Study Series (Survey Methodology #2014-02). U.S. Census Bureau. Available online at http://www.Census.gov/srd/papers/pdf/ssm2014-02.pdf

O’Hare, W.P. (2014). “Historical Examination of Net Coverage Error for Children in the U.S. Decennial Census: 1950 to 2010.”Center for Survey Measurement Study Series (Survey Methodology #2014-03). U.S. Census Bureau. Available online at http://www.Census.gov/srd/papers/pdf/ssm2014-03.pdf.

Passel, J. (1991). “Alternative Estimates of Black Birth Corrected for Under-registration: 1935-1980” The Urban Institute, Washington, DC.

Population Reference Bureau (2020). “Predicting Tract-Level Under Undercount Risk for Young Children” O’Hare W.P., Jacobsen, L. A., Mather, M. and VanOrman, The Population Reference Bureau, Washington, DC., https://www.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/us-Census-undercount-of-children.pdf

Robinson J. G., Das Gupta, P. and Ahmed, B (1990). “A Case Study in the Investigation of Errors in Estimates of Coverage Based on Demographic Analysis: Black Adults Aged 34 to 54 in 1980, Paper presented at the American Statistical Association Annual meeting Anaheim, CA, August.

Robinson J. G., (1997).” The Differential Undercount of Adult Black Men: Is it a Myth?” Internal Census Bureau Memorandum, November 3, U.S. Census Bureau Washington DC.

Runes, C. (2019). “Following a long history, the 2020 Census risks undercounting the Black population,” the Urban Institute, Washington DC., February 26

A paper describing the database and how to use it is available here https://countallkids.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/How-to-Use-the-PRBs-Young-Child-Risk-of-Undercount-Database-2.20.20.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau (2012). 2010 Census Coverage Measurement Estimation Report: Summary of Estimates of Coverage for Persons in the United States DSSD 2010 Census Coverage Measurement Memorandum Series #2010-G-01. U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC.

U.S. Census Bureau (2019), Investigating the 2010 Undercount of Young Children – Summary of Recent Research,” O’Hare, W .P., Griffin, D., and Konicki, S., 2020 Census Memorandum Series, U.S. Census Bureau, https://www2.Census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/program-management/final-analysis-reports/2020-report-2010-undercount-children-summary-recent-research.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau (2016).”Investigating the 2010 Undercount of Young Children—A New Look at 2010 Census Omissions by Age,” Howard Hogan and Deborah Griffin issued July 26, 2016., U.S. Census Bureau, Washington DC. https://www2.Census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/program-management/memo-series/2020-report-2010-undercount-children-ommissions.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau (1988).”1980 Census of population and housing. Evaluation and research reports. The coverage of population in the 1980 Census,” by Robert E. Fay, Jeffrey S. Passel, J. Gregory Robinson: with assistance from Charles D. Cowan.

U.S. Census Bureau (1991). “Summary Table comparing the Census, Post Enumeration Survey, and Demographic Analysis Estimates of the U.S. Resident Population on April 1, 1990.” By J. Gregory Robinson Memorandum for Paula J. Schneider, Chief, Population Division, June 13

West, K. Devine, J., and Robinson, J.G. (2014) An Assessment of historical demographic analysis estimates for the Black male cohorts of 1935-39. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Statistical Association, Boston, MA.